Ethics, aesthetics and dialog in Gestalt therapy

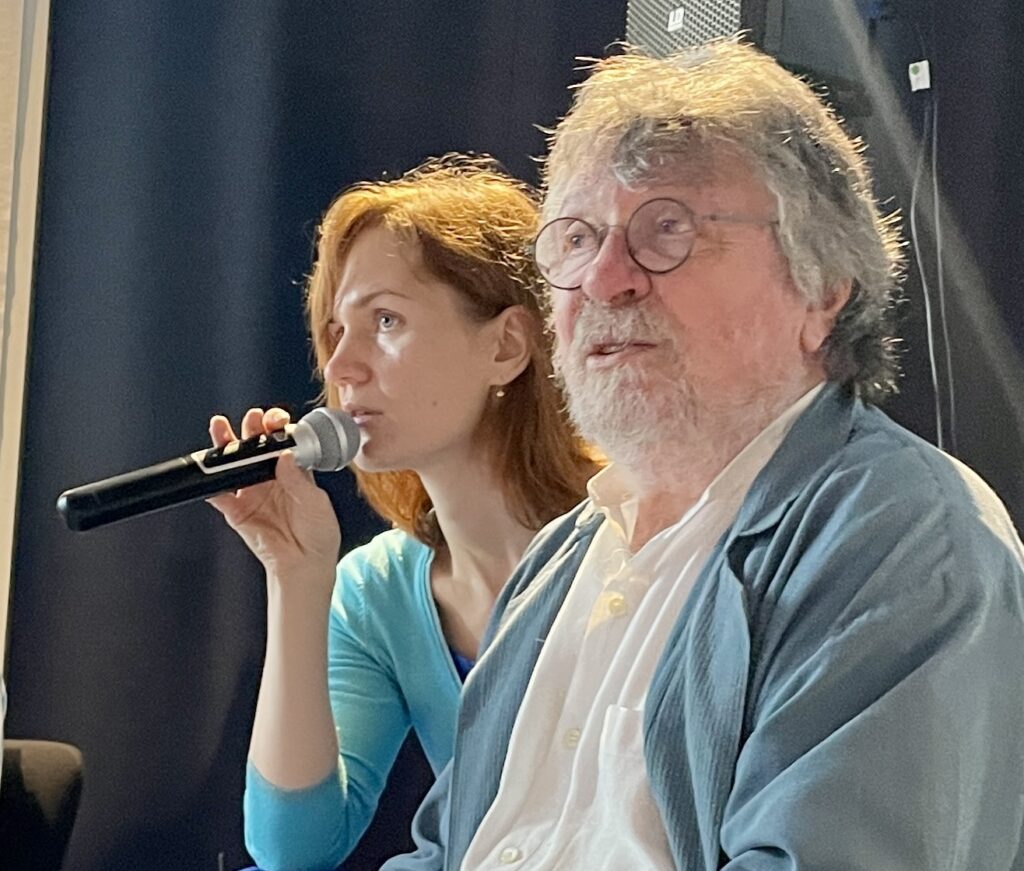

Interview with Jean-Marie Robin at the Dialogues de Toulouse, Toulouse, France, May 2023.

Olga Kadysheva (OK): Now to begin the interview, Jean-Marie, I would like to know what you would like to say about yourself and your path in Gestalt therapy. How would you describe it? I realize that it may not have been short, but please describe briefly the main events that led you to Gestalt therapy.

Jean-Marie Robin (JMR): In ’67 I started working as a psychologist. But Gestalt therapy came later in France, somewhere in the mid-70s. And before that, the only choice to be a psychotherapist was either psychoanalysis or psychodrama. And then I was introduced to client-centered therapy. And that was also called expression therapy, expression therapy. I did a lot of that with my friends. And when I came across Gestalt therapy, probably in ’75, I immediately felt that this was something that I was interested in. And it was something that allowed me to connect all the things that I had previously encountered in other approaches and kind of make this kind of spine. Structure to create. I studied in several programs and the first one was what was called at the time the California approach, the California style, that’s the only form that existed in the beginning. And there was very little theory, very much experience. And then I studied at the Cleveland Institute, which was coming to conduct a program in Belgium. And in those days, if I may say so, the daddy of Gestalt therapy was Irwin Polster, the Polster family. And all the training was based on their approach, their theory and their concepts. And after I was trained in that approach, I practiced for several years and I was ready to quit Gestalt therapy because I had reached the limits of that approach. And I was lucky then, I heard about another approach of Gestalt therapy that was still in the shadows. And this was actually a current developed by its creators, Perls, Laura Perls, Goodman and Isidore Frome. And I met Isidor Fromm, who was sometimes in Europe, and he agreed to take me into a small group that he was running, about 5 or 6 people. And that’s when I discovered another form of the Gestalt, the one that the creators came up with. And I discovered Goodman’s book and the founders’ book, which I had never even heard of before. And I’ve been practicing this approach for about 45 years now, and I don’t want to leave it and I don’t feel like I’ve explored everything. And of course this model is not finished and not fully explored, but I think this is a very good and, you could say, revolutionary direction.

And it so happened that in the early 80s, together with some colleagues, we founded the European Gestalt Association. You probably know that somewhere around the 90s I was the president of this association, I don’t remember exactly which years. It was around the time when the Iron Curtain was torn down. And so I managed to invite Russian-speaking people to a conference in Paris. And after that I was invited to Moscow to conduct training, and I had the honor and pleasure of training the first group of Gestalt therapists in Russia.

And it was with people who then founded institutes, MGI, MIGIP, Oleg Nemirinsky from St. Petersburg. And that’s how I got acquainted with your community, which then began to invite me to Ukraine, first to Kiev, then to Dnipro, to Odessa, to Lviv, to Crimea, when it was still a free territory.

OK: A lot of our Gestalt therapists have been coming to you, well because you run supervision groups, on your premises, right in your home.

JMR: Because I live in the countryside, one of the bands just offered at one point to come to my place for the summer and there’s a lot of these sort of small hotels around that people can stay in, very much like family hotels. And, you know, that’s what I prefer, if you have to choose between that kind of opportunity and zoom.

Michael Baytalsky (MB): Jean-Marie, this interview should be called “ethics, aesthetics and dialog in Gestalt therapy. I have a question: which of these concepts would you like to talk about first? Ethics, aesthetics, or dialog?

JMR: Of course, without a doubt, my favorite concept of these three is aesthetics. And I remember that somewhere in ’81, ’82 at a congress, my presentation was called Ethics and Aesthetics in Gestalt Therapy. And I must say, of course, that the concept of aesthetics has been very fashionable in Gestalt therapy for the last few years. And it would be good to come back to it and discuss it, because there are very diverse concepts, diverse perceptions. At the beginning there was a little reflection by Laura Perls, who talked about the word Gestalt being an aesthetic concept. But she didn’t really elaborate on that. And I think she had a little text where she compared a psychotherapist to an art critic. But it’s also important to think about what we call ourselves, we call ourselves psychotherapists, and psychotherapy is what we do, Gestalt therapy. And what does it mean when we say we work in Gestalt therapy. Does it mean that we don’t do psychotherapy, we don’t do psychotherapy, we don’t do psychotherapy of the psyche, but we do Gestalt therapy? In other words – we are dealing with how people create forms for their existence. And what forms people can create, it can be lifestyles, it can be patterns, some ways of being, life choices – all these are forms. And in later years, some colleagues have described the idea of aesthetics in very particular ways. For example Joseph Zinker – you probably know his work – he was also very insistent on form, on the concept of form, and he talked a lot about beauty. This was somewhere around ’77.

I also often talk about Michael Vincent Miller. This man has become one of my greatest friends in Gestalt therapy. He wrote an article called, “Notes on Art and Symptoms.” And he wrote a lot about various artists, artists, and he talked about how art is this kind of door that allows you to enter into pathology. And he took a lot from what Otto Rank had said, who thought that the neurotic was a failed artist. And he believed that we create a symptom for ourselves, roughly like a work of art. Of course, here I’m talking about the process, not the content. And subsequently, when there was the first conference in the European Gestalt community in the ’80s, I did a conference on the aesthetics of psychotherapy. And this is a theme that has lived in me all this time.

Why? Because aesthetics is such a concept that was invented around the 17th century by a second or third rate philosopher, his name was Baumgarten, he was interested in developing another form of knowledge. He believed that not only is cognitive, cerebral, shall we say, knowledge important, but that there is also knowledge that we get through our senses. And that what we receive, what we recognize through the senses, is something less complex, less refined than our intellectual knowledge, but that sensation and what we feel is the starting point of any experience.

And you’ve probably noticed that the favorite phrase of Gestalt therapists when they talk to clients is “how do you feel?”. And I want to hope that people aren’t saying that phrase because they can’t think of anything else. And the idea is that everything that happens starts in the sensations, in the body, in what we perceive through the senses. And after that we need to do the work of transformation.

Estesis is really a sensation. It’s not about beauty. It’s not about beauty. Everybody, for example, you know the wordanesthesia. Anesthesia doesn’t mean the absence of beauty, it means the absence of sensation. And when this concept was invented, of course, the whole art world jumped on it, mastered it, because the art world is of course such a paradigm in aesthetics, because it’s such a place where you have to feel first.

I do not agree at all with the two concepts that are circulating in the world of psychotherapy about aesthetics. The first concept is about beauty, about the beauty of a symptom, for example. And there’s a second place that I don’t agree with, people say that if aesthetics is about feelings, then I can feel the other person. And there’s a whole strand of people who think that they can feel what someone else is feeling right now and that it will be true. If I’m across from you and I’m feeling sad – it’s because you’re sad. We can talk about aesthetics for hours, but we don’t have a clock.

MB: I want to ask a clarifying question. And what categories would you use to describe the aesthetic, if not beautiful or ugly. What other categories, how do we expand our vocabulary in describing the aesthetic.

JMR: A colleague at the New York Institute picked out all the vocabulary that Perls and Goodman used. All the words they used to illustrate the word “gestalt.” And he noticed that all the words that the authors use to describe gestalt are aesthetic words. Clarity, sharpness, vividness, contours. People are looking for words. You said the word “categories,” I hate “categories.”

When Laura Perls speaks of the psychotherapist as if the psychotherapist were an art critic, we can use a vocabulary that we awkwardly use, but that we can use to describe art. It is a sensual vocabulary, a vocabulary we use to describe the figure-background relationship.

And if we think about it, a lot of the words we use are also interesting from the point of view of the art world. For example, I’ve been working a lot on what is called the “field paradigm”. I have been working on this concept for a long time and for many years I used to use this expression “field paradigm”, but then I started to say to myself that there are more interesting words, because we can look at the field as a perspective. And perspective is, again, a word that comes from the dictionary of art. That’s the kind of thing.

OK: Thank you, Jean-Marie. What would you say about your view, your perception of the sensual and aesthetic perception of dialog. And since we’re talking about the field paradigm and the field perspective, what does dialog do to the field. What does dialog do to you personally. With a client. With a group. How it changes you.

JMR: I think this is a very complex topic. Very important and very interesting. Now a lot of people use the words relational perspective, field perspective, dialogical perspective. These are not quite the same, not quite equivalent words. Of course these are such attempts to get out of the intrapsychic or individualistic approach. Now in France all psychotherapists are called relational psychotherapists. And a therapist who works with protocols, with prompting phrases for the client is also a relational perspective. But it’s not quite the same as the dialogic form.

And the problem with the concept of dialog is that there are constant references to Martin Buber’s concept. And when he talked about the concept of “I-you” – it is a very interesting concept, but Buber looked at it in a much more mystical way. In order for there to be a real dialog, I see mainly two levels here. I will look at my client as a human being who is neither more nor less valuable than I am. It is absolutely clear in my mind that as human beings we are equal. However, in the situation we will be in, that equality will not exist. Because he comes to me, he has suffering, he has in my direction turned expectations. And in the way Martin Buber saw it, the relationship between “I” and “you”, who are equal persons here, cannot take place here, because it is not yet the case in therapy. And when we talk about the “I-you” relationship it will be such an indicator that therapy is about to end or has already ended.

I will never forget how Isidor Fromm answered my question about how to realize that therapy is over. He had many answers to that question, but one of the ones he told me was that therapy is over when the patient starts saying something interesting. And I had to think for days about what he told me, because he spoke like a Zen teacher, and you had to think about his phrases like koans. And speaking of that, what you should understand is that if a client tells me about a book or a movie or something else and when the therapy is not finished yet, I will not be interested in the book or the movie, but how the client uses it to tell me something about himself. And when the therapy is over, the client will tell me the truth about the book and it is about the book that I will listen. Can you feel the difference?

MB: I will try to continue this theme. Still, how would you describe the dialog that takes place in the field. How it affects the field. What is dialog, in general. Is there any value in it. Is there anything of value for you behind this concept.

JMR: There’s a big problem intheway you phrase it when you say “in the field.” There are so many concepts of the field in the Gestalt therapy marketplace that everyone uses the term, but it never means the same thing. I often tell my students that I’ve been a Gestalt therapist for about 45 years now, and from the beginning I was attracted and intrigued by the field perspective. And my trainers initially used the concept of “field” more as a slogan and couldn’t really explain or show what it meant. And if you look at Perls’ works, at the films at the beginning of his practice, in the Esalen years, for example, there is no field perspective there. And there we of course see an intrapsychic perspective, where the therapist knows what is good for you. Of course you can do good work that way too, that’s not the question, but it’s a different perspective.

And when I started doing field perspective, I was terrified at first to dive into it. Because I already felt beforehand that it would be a revolution in my life, in my style, in my views, in everything. And I was also afraid of being isolated, of being alone in my community. And then I noticed that the field of Gestalt therapy was stirring a little bit around. And I’m not going to lie to you, all these years I’ve been writing about the field, writing articles, studying it, and every time I thought – now I understand what the field is! And six months later, it all comes crashing down. No, I didn’t get it, it’s not that. And I’d start all over again. And then six months later, I finally figured it out again. And everything collapses again.

I have lived it ten, twenty times. And so for today I think I have realized what the field is, well, or you could put it this way, I made a choice. And when I say, “I made a choice,” it’s such a polyphonic and polysemantic concept that I just chose.

And now I realize that every time I misunderstood the concept of field, it was when I gave it a geographical connotation. As if the field is a unit that has boundaries. And when you say “in the field,” you’re creating a geographical unit like that. It’s in the field or it’s not in the field. What’s not in the field? From the moment it is named, it will arise, for example, in my field of awareness. And there is also a very important element that among all the possible definitions of field, Perls and Goodman chose to talk to us about a certain type of field. And they labeled it theorganism-environmentfield. It’s not a field, it’s an organism-environment field. And a field doesn’t just exist. It’s someone‘ s field, a field belonging to someone.

It is very important that there is a field of something, it can be the field of psychotherapy, it can be in the field of my neighbor, “in the field of something”. And the field “organism-environment” is the field of the organism and what is its environment. And the organism is that which manifests out of the field and to the same extent the organism and creates the environment that will be its environment. It is such a reciprocal movement. And it is an indivisible movement. And for me, the correct understanding of the field is a way that can be used to talk about the human being, the human being, and to consider it as inseparable from its environment.

Perls and Goodman in their book say “from the field”, they don’t say “in the field”. It’s like the difference between being “in Toulouse” or being “from Toulouse.” If I say I’m in Toulouse, it’s that kind of city, a geographical place. And if I say I’m from Toulouse, I consider myself something produced in Toulouse – I come from there.

And we are “of the field.” And it turns out that today there is such a very large movement in Gestalt therapy that brings together people who talk about the collaborative field. But it’s all absurd. Because if it is an organism-environment field, it cannot be a joint field. We are in the same environment – that’s true – but if the field is “organism-environment” then none of us will have the same identical field right here and now. For example, here if we talk about the visual field, the field of vision, none of us will have the same vision when we are in the same environment.